|

| Fig 1 - Modern gated community |

Although gated communities are eulogized by residents, developers, and real estate agents for providing safe family spaces and secure financial investments, they have received a largely negative press from academics and the media, who perceive them as private fortresses that destroy the vibrancy of the city through their exclusivity. (Lemanski 2008)The dominant view -- both scholarly and popular -- emphasizes security and fear. People are shutting themselves away in gated communities to keep out crime and undesirables. The spread of gated communities is said to produce alienation and anomie among residents, and a socially divided or segregated urban landscape (Blakely and Sneider 1997; Low 2001). Some research, however, challenges the security/fear interpretation of modern gated communities. Andrew Kirby and colleagues (Kirby et al. 2006), for example, report that in a sample of Phoenix gated communities, "residents are not alienated" (p.29), and the communities are not responses to a "culture of fear."

|

| Fig 2- Informal neighborhood gate, Lima |

The fear/security factor may, in fact, be more prominent in gated communities in poor neighborhoods of cities in the developing world than in modern U.S. or European cities. In Peru, enclosed areas are being established long after initial construction, by the residents themselves. Jörg Plöger (2006) studied neighborhoods in Lima, Peru, and found that most neighborhoods are "enclosed" or sealed off (with barriers and fences) by their residents for reasons of security (figure 2). These gates are installed not by developers or municipal authorities, but by the residents; they are informal, not formal, urban features. And even Dharavi, the Mumbai slum (of Slumdog Millionaire fame) where people are living in extremely close quarters, is the setting for many fenced-off residential zones. Jan Nijman (2010) explores how Dharavi challenges a number of standard notions in urban studies, a field whose models are based overwhelmingly on modern western cities.

|

| Fig. 3- Chinese walled compound |

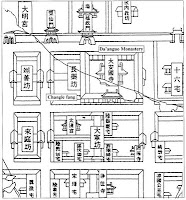

These studies of the developing world are important for establishing a broader comparative perspective for gated communities. When we consider the past, the diversity of forms and meanings of gated communities increases even more. It turns out that gated communities have been common in Chinese cities for more than a millennium (Xu and Yang 2009), and they have been prominent in Mexico from the time of Spanish conquest until the present (Scheinbaum 2008). Figure 3 shows a traditional Chinese walled compound (i.e., a gated community). Interestingly, these features resemble Inka walled compounds (called kancha) in Peru (figure 4). There is no historical connection at all between the Chinese and Inka examples; these are independent adaptations to what were probably similar urban forces and conditions. My guess would attribute this similarity in form to the importance of kinship and lineage in Chinese and Inka society. Several generations of families live together,

|

| Fig 4 - Inka Kancha |

As in most premodern cities, the Chinese compounds were probably designed by their residents, and built either by the residents or by builders contracted by the residents. We know less about the construction of Inka compounds. The Inka state was strongly bureaucratic, and officials supervised and carried out many activities that were left to individual families in most early societies. Maps of Inka settlements show that these kancha units are highly standardized, perhaps because of central planning (Hyslop 1990).

|

| Fig 5- Walled compounds in Chang'an |

|

| Fig 6- Old neighborhood gate, Jerusalem |

|

| Fig 7 - Hohokam walled compound |

|

| Fig 8 - Iron Age walled compound |

These comparisons have intrigued me for a number of years. What is needed is a comprehensive comparative study of walled compounds / gated communities in the premodern world. Synthetic studies like Grant and Mittelstaedt (2004) are a good place to start. Perhaps we can figure out some of the social parameters of these features, and allow archaeologists to link the spatial layouts to social processes. Or perhaps the situation is just too messy and diverse. But until someone attacks this problem, we will never know.

References

Abu-Lughod, Janet L.

1987 The Islamic City: Historic Myth, Islamic Essence, and Contemporary Relevance. International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 19:155-176.

Blakely, Edward J. and Mary G. Snyder

1997 Fortress America: Gated Communities in the United States. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Grant, Jill and Lindsey Mittelsteadt

2004 Types of Gated Communities. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 31:913-930.

Heng, Chye Kiang

1999 Cities of Aristocrats and Bureaucrats: The Development of Medieval Chinese Cityscapes. University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu.

Hyslop, John

1990 Inka Settlement Planning. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Kirby, Andrew, Sharon L. Harlan, Larissa Larsen, Edward J. Hackett, Bob Bolin, Amy Nelson, Tom Rex, and Shapard Wolf

2006 Examining the Significance of Housing Enclaves in the Metropolitan United States of America. Housing, Theory, and Society 23:19-33.

Lemanski, Charlotte

2009 Gated Communities. In Encyclopedia of Urban Studies, edited by Ray Hutchison, pp. Article 109. Sage, New York. http://www.sage-ereference.com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/urbanstudies/Article_n109.html.

Low, Setha M.

2001 The Edge and the Center: Gated Communities and the Discourse of Urban Fear. American Anthropologist 103:45-68.

Nijman, Jan

2010 A Study of Space in Mumbai's Slums. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 101:4-17.

Plöger, Jörg

2006 Practices of Socio-Spatial Control in the Marginal Neighbourhoods of Lima, Peru. Trialog: A Journal for Planning and Building in the Third World 89(2):32-36.

Scheinbaum, Diana

2008 Gated Communities in Mexico City: An Historical Perspective. Urban Design International 13:241-252.

Xu, Miao and Zhen Yang

2009 Design History of China's Gated Cities and Neighbourhoods: Prototype and Evolution. Urban Design International 14:99-117.