Follow me in a hypothetical situation here. Suppose you are an archaeologist who has found some complex settlements in a region (like Amazonia) whose indigenous inhabitants are traditionally thought not to have constructed urban or state societies. Here are two paths one might follow. First, you could read the literature on early urbanism, pay attention to how various concepts and models are operationalized in other regions, and then apply those insights to your data. You could test whether they match urban settlement in other areas, and explore whether urban concepts help advance knowledge of the setting. This would be a scientific approach to analysis and argumentation. Or, second, you could start by making a sensationalist claim that you have found urban sites, but without providing a definition of what you mean by urban.

I will start with the first option (the one not followed by Rostain et al). The most widespread urban definition is the sociological definition from Louis Wirth: a city is a permanent settlement with high population, high density, and social heterogeneity. These sites are not populous enough or dense enough to qualify. The authors report a platform density within settlement of 125 platforms/km sq; that is 1.25 platforms per hectare. If these were houses (the authors say this), and then at 5 persons per house, the density would have been 6 persons/ha, which is about the same as Tikal and other Maya cities. This low density is not too surprising; Maya cities also fail to fit Wirth’s definition. What about the alternative functional definition? Cities are settlement that contain activities and institutions that affect a broader hinterland (these are called ‘urban functions’). Maya settlements certainly fit here; palaces (and epigraphy) signal political rulership that extended beyond individual capitals, and big temple-pyramids signal religious functions, if people came from nearby smaller sites to ceremonies. These definitions are reviewed by lots of authors; for my contributions, see: (Smith 2020; Smith 2023:chapter 1).

So, we can ask whether Sangay (the largest and most complex of the reported sites) had urban functions? The authors fail to present evidence for this. They make a claim that the various sites, large and small, showed “architectural and spatial homogeneity” (p.186). That would be a strong argument AGAINST an urban interpretation, since one of the features of urbanism is that different kinds of settlements have different kinds of activities and institutions. If Sangay had the same set of public buildings and spatial layout as smaller sites, I’m not sure how one could justify the label urban.

Anyway, these are just some things that I would investigate if I were working with the data on these sites. They are certainly fascinating sites, and a site does not have to be considered “urban” for it to be interesting and important. Indeed, one of the features of my own theoretical approach to urbanism is that it is more productive to investigate a wide range of sites for urban and urban-like features than to try to police the boundaries of urbanism to find ways to keep out certain early sites. See my book on this approach (Smith 2023)

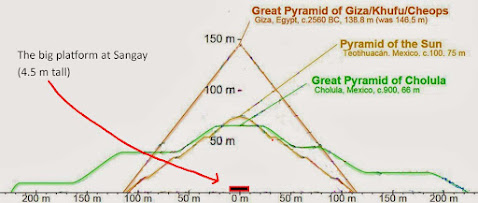

The second option—to make a sensationalist claim that one has found urban sites, without bothering to define urban or its material manifestations—is the one followed by Rostain et al. This may have led them to submit to the journal Science, whose coverage of archaeology has long emphasized sensational finds over scientific rigor (see my earlier posts, on the blog Publishing Archaeology, on problems with archaeological coverage in Science:: Post, "Rejected by Science" post: "How archaeology is distorted by Science magazine"). The authors close the paper with the claim that the areas of the central zones “are comparable in size to those of other great cultures of the past, such as Mexican Teotihuacan or the Egyptian Giza Plateau (page 188). I'm not sure why this is of theoretical interest, or what it has to do with a claim of urbanism; to me it is a piece of information that does not help in the task of analyzing these sites. Maybe this claim made sense to the editor and the single reviewer. What if we make a comparison that does have some theoretical content? My diagram shows the height of some of the major pyramids of those other cultures, with the reported height at Sangay (4.5 m tall) shown in comparison. Why is this theoretically interesting? Read just about anything on early urbanism.

We seem to have another case where the journal Science has published an unscientific analysis. Perhaps if your definition of science for archaeology focuses on the use of scientific techniques from the natural sciences, then this is science. But if your view is that science is an epistemology—a way of generating knowledge based on precision and operationalization of concepts, based on testing of hypotheses, then this paper is hardly scientific in orientation. Some of my views on these concepts of science can be found in: (Smith 2017), and in the blog posts that preceded that paper. There are three posts;

Heckenberger, M (2013) Tropical Garden Cities: archaeology and memory in the Southern Amazon. Revista Cadernos do Ceom 26(38):185-207.

Heckenberger, MJ (2009) Lost Cities of the Amazon: The Amazon Tropical forest is not as Wild as it Looks. Scientific American 301(4, October):64-71.

Heckenberger, MJ, JC Russell, C Fausto, JR Toney, MJ Schmidt, E Pereira, B Franchetto and A Kuikuro (2008) Pre-Columbian Urbanism, Anthropogenic Landscapes, and the Future of the Amazon. Science 321:1214-1217.

Prümers, H, CJ Betancourt, J Iriarte, M Robinson and M Schaich (2022) Lidar reveals pre-Hispanic low-density urbanism in the Bolivian Amazon. Nature 606:325-328.

Smith, ME (2023) Urban Life in the Distant Past: The Prehistory of Energized Crowding. Cambridge University Press, New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment